Rapid research is ever more relevant for evaluators, but there is insufficient discussion about the practical challenges of working ‘rapidly’.

Manni Sidhu explores what he learnt about these issues when leading a workshop with Tom Ling (RAND Europe) at this year’s UK Evaluation Society (UKES) conference.

Manni Sidhu explores what he learnt about these issues when leading a workshop with Tom Ling (RAND Europe) at this year’s UK Evaluation Society (UKES) conference.

Describing and discussing the benefits of rapid research is a highly relevant subject, especially when working with colleagues across the NHS where timely learning from evaluation evidence is needed to inform the implementation of rapidly changing health policy. As the context for innovations often changes during implementation, there is a need for on-going feedback from evaluation studies to support possible scaling up and roll-out across the wider health system.

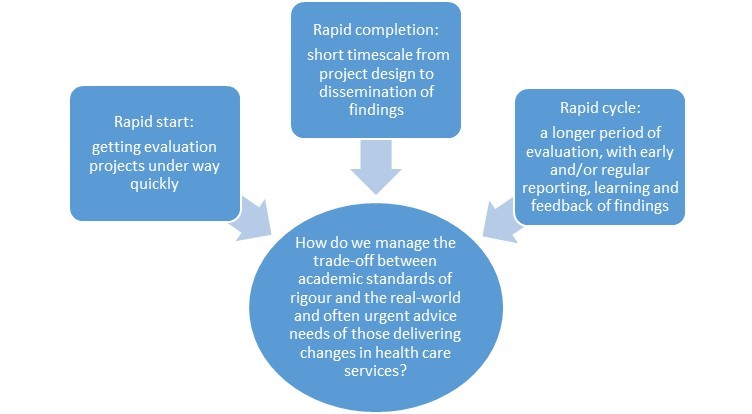

However, policy makers’ desire for more timely evidence has to be balanced with important questions of how to ensure the quality, rigour and robustness of evaluation findings. This raises a critical question for evaluators: how do we manage the trade-off between academic standards of rigour and the real-world and often urgent evidence needs of those delivering changes in health care services?

‘Rapid’ can be defined in a number of ways. Here at the National Institute of Health Research funded Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation (BRACE) Centre we conduct rapid evaluations of promising new services and innovations in health care. We understand ‘rapid’ not as a single approach but the context within which our research is completed, namely to examine not only what works, but also how and why things work (or don’t), and in what context we can produce rigorous, timely and useful evidence to inform the transformation of services.

Alongside this understanding of ‘rapid’, we have to consider legitimate concerns from academic researchers and funders about the reasons for shortening project timescales and the potential impact of doing so on the rigour and quality of findings. There is however an emerging body of evidence that some research processes can be undertaken using rapid approaches, without a knock-on impact on rigour and quality. For example, some have suggested innovative ways of undertaking rapid analysis of data and there is growing interest in rapid ethnography (the study of people, cultures and their customs). Meanwhile others have suggested rapid ways of standardising data collection and analysis processes.

Certain evaluation processes cannot however be rushed, in particular building relationships with those carrying out service innovations, agreeing ways of working with those involved in the research, and ensuring thorough scoping and planning of the study itself.

For attendees at the UKES workshop (researchers and evaluation consultants), a core concern was how to build and maintain working relationships within an evaluation project that support the needs of those commissioning or taking part in the research. They felt as evaluators they face a particular challenge in choosing and using an appropriate mix of methods to collect and analyse data - and disseminate findings - in a pragmatic way that meets the often impatient and evolving needs of those commissioning the work.

For example, a rapid study can involve significant early scoping of literature and approaching key stakeholders for expertise, holding project design workshops, sharing learning and giving regular feedback. While long reports are simply not going to be read by most busy practitioners and policy makers, but short, focused and digestible summaries using infographics and videos are typically much more practical as a way of maximising dissemination of findings.

So, how is BRACE managing this trade-off between academic standards of rigour and real-world evidence needs through our working relationships with practitioners and policy makers? We are using a range of rapid methods in our projects such as (but not limited to) rapid scoping reviews to focus our research questions, quick turn-around for preliminary analyses, and holding data analysis workshops with policy analysts and academics to interpret findings.

Indeed, we seek always to involve the people we are studying (e.g. health care staff, managers, service users) closely in the different stages of each rapid evaluation, for example engaging them in the design of a project, inviting them to workshops to discuss the development of research questions and exploration of early findings, and helping us determine how best to disseminate our conclusions and insights in a timely – indeed rapid - manner.

With three rapid evaluations underway, BRACE colleagues are learning how best to keep rigour and rapidity in balance using an innovative mix of methods, building strong relationships within the service innovation community, as well providing real-time feedback to policy analysts and academics to share findings.

Manni Sidhu Is a Research Fellow at the Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham and is a member of BRACE.