The University of Birmingham was established by the granting of a Charter in May 1900; the first Civic University. The basis of the University was the existing Mason and Queens colleges, Mason for Science and Engineering, Queens for Medicine, Theology and Arts; the two had combined in the early 1890's. To the vision and drive of Mason was added the drive and determination of Joseph Chamberlain, at that time Minister for the Colonies; he had considerable experience of local politics in Birmingham.

The University of Birmingham was established by the granting of a Charter in May 1900; the first Civic University. The basis of the University was the existing Mason and Queens colleges, Mason for Science and Engineering, Queens for Medicine, Theology and Arts; the two had combined in the early 1890's. To the vision and drive of Mason was added the drive and determination of Joseph Chamberlain, at that time Minister for the Colonies; he had considerable experience of local politics in Birmingham.

The creation of the University of Birmingham was of enormous significance for higher education outside of Oxbridge. The previous model had been a federation of colleges with degree awarding powers vested in a University. Victoria University, chartered in 1880, had constituent colleges; Owens in Manchester, Liverpool college, Yorkshire college in Leeds. London University awarded degrees for study in various colleges. The Charter to Birmingham was a new understanding of University, the federal pattern was overtaken. Within a decade Chamberlain?s Birmingham model became the standard pattern, the ?Civic? model; Liverpool 1901, Leeds 1904, Sheffield 1905, Bristol 1909.

In July 1900, following the May Charter date, Lord Calthorpe offered the new University 25 acres of land on the Bournbrook site of his Edgbaston estate, thus NOT only a new University, a CAMPUS as well.

The University started life at Mason College in the City Centre, Edmund Street, and continued to use those buildings for many years. Site work at Bournbrook began in 1901, departments moved into the radial blocks in 1905, at which time the superstructure of the Great Hall was started. The departments and the courses on offer were essentially transfers from Mason College but there were two innovations,

BREWING and MINING. The 1900 vision was a University which would shape itself on the needs of a manufacturing town and produce graduates fully conscious of conditions of national prosperity. These innovations in practical science were the result of a specific Chamberlain technique of encouraging local companies and industries to sponsor courses in their own area of interest. The British School of Malting and Brewing, later named the School of Brewing and Fermentation, was set up in 1900 with a £28000 grant from the Midland Association of Brewers.

Such innovations were the target of traditionalists. The Pall Mall Gazette described Birmingham as a 'Bread and Butter' University which would produce graduates schooled in 'Tariff and Values'. Punch and the Westminster Gazette presented Brewing at Birmingham as a huge joke. Oxford undergraduates wrote ditties such as

He gets a degree in making jam

At Liverpool and Birmingham

It was no joke, Brewing was a major Midlands industry, Birmingham would produce graduates the industry needed.

Another major industry of the Midlands was Mining. Richard Redmayne was appointed Professor of Mining in 1902 and served until 1908 when he was appointed Chief of the Mining Department at the Home Office, the Chief Inspector of Mines. Whilst at Birmingham he developed the model mine which was completed in 1905; the slope of the land on the South side of the campus enabled construction of a mile of mine galleries with different levels and roads; there was instruction in coal winning, ventilation and surveying. Birmingham mining graduates were exempt from the statutory requirement for extra training in underground colliery management. Birmingham was producing graduates the industry needed.

Redmayne's replacement was John Cadman, a serving Government Inspector of Mines, appointed as the Professor of Mining at the age of 31. He held the Chair from 1908 to 1922.

VERY significantly for Chemical Engineering Cadman's interests included the Mining of OIL. There are many 'oil' connections identifying this:

- from 1911 students entered the Mining department to study oil mining alongside coal mining

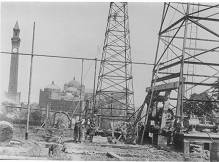

- oilfield drilling rigs ordered in 1912 [installation site was between the current Chemical Engineering buildings and the University station]

- first drilling instructor appointed 1913

- Cadman appointed member of expert commission sent to assess the Persian oil fields in 1913

- 1916 Cadman appointed Chairman of the Inter-Allied Petroleum Council

- 1917 Cadman appointed Director of His Majesty's Petroleum Executive [reporting directly to Lloyd George's War Cabinet]

- 1920 Cadman stood down as Dean on appointment as Adviser to the Cabinet on questions affecting Coal and Petroleum

The commission to the Persian oil fields in 1913 is most interesting. The key members were Rear-Admiral Sir Edward Slade and John Cadman, Professor of Mining at Birmingham University and Petroleum adviser to the Colonial Office. The background factors to that visit were:

- the Navy experimented with oil as a fuel from 1898 and had some oil fired ships

- the Anglo-Persian oil company was launched in 1909 following the discovery of the Persian oilfield

- Winston Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911, he was a convert to oil as the fuel for Navy ships

- in 1912 Anglo-Persian was in need of new finance and approached Churchill and the Navy

- 1913 the commission was sent out, reported in April 1914 and 6 weeks later two agreements were signed

These agreements were

- £2million Government capital to Anglo-Persian in return for a majority shareholding

- contract for 40 million barrels of fuel oil to the Admiralty over 20 years

There can be no doubt as to the link between Birmingham and the oil industry at that time.