Meet Your Peers - Courtney Brightwell

Courtney Brightwell on Schools buying energy

Schools across England face a challenge to buy goods and services that represent value for money in terms of the price paid, quality of the product and its ease of access. The best deals, for example for energy, will often be beyond the reach of schools without significant procurement capability.

This project explored how schools could save on their energy bills, which total over £600m per year in England. This challenge is set to increase further as energy prices have risen to record levels in 2022, due to low levels of gas storage in Europe and lower pipeline imports from Russia, and the importance of gas-fired power stations.

Key points:

- The costs of energy are beginning to dominate school budgets and the lack of transparency and unpredictable nature of the size and frequency of bills prevents good financial planning.

- The energy market is complex involving major energy suppliers on one side, and schools with limited market knowledge and experience on the other.

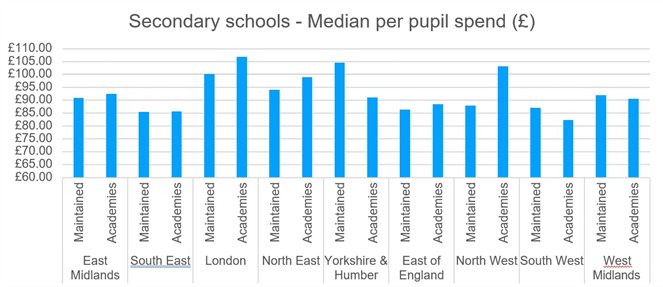

- Energy costs vary markedly between schools. Median costs per pupils are highest amongst secondary schools, particularly in London (over £100 per pupil). Primary schools pay much less (around £50 per pupil) and special schools much more (over £250 per pupil).

- Schools often use energy brokers or their local authority, as they lack specialist understanding of the energy market. Many are concerned whether these third parties are truly focussed on getting the school the best energy deal.

- Schools can save energy and reduce costs by improving the energy efficiency of their infrastructure and influencing the behaviours of staff and pupils. This commonly includes the use of LED lighting, solar panels, and replacement boilers.

- More can be done to help schools be intelligent buyers and users of energy. Government could make it easier for schools to switch supplier and ensure more transparent pricing information.

- There may be potential to develop a national aggregated energy deal for schools.

Background

Many school staff are concerned regarding how the costs of energy are beginning to dominate school budgets and that the lack of transparency and the unpredictable nature of the size and frequency of bills prevents good financial planning. This research addresses the questions: “What problems do schools experience when buying energy?” and “Why do they experience these problems?”.

The energy market is complex and includes many major suppliers who are large private companies, so the market quite starkly poses schools, often with limited market knowledge and experience, against large often multi-national companies. It raised the question whether public funding to schools is being swallowed up in part by the exploitation of schools’ weak buying position.

Following a detailed literature review, interviews were completed with 11 School Business Professional staff from a variety of school types (e.g. local authority, academy, special and private) and education phase (primary and secondary). In addition, national data on expenditure in over 20,000 schools was analysed.

What we knew already

The UK (along with the USA and Canada) has increasingly decentralised decision making in education from local authority to school level. Interestingly the opposite trend can be observed in Southern and North West Europe and parts of Asia.

The existing literature shows that energy consumers are most likely to switch supplier for an improved deal in countries with more established liberalised energy markets, and where tariff calculators and customer ratings of suppliers are available. The availability of the consumer having time available to search for savings is an important factor. Barriers to switching include the complexity of energy tariffs, low attention to the issue of energy prices, expected costs of switching and lack of switching experience. Many of the key challenges consumers face in securing a good deal are magnified in the school setting, since the business energy market does not offer fixed unit costs for energy, nor access to handy price-comparison tools.

Variations in energy costs

Analysis of the national dataset demonstrated that energy costs per pupils are highest amongst secondary schools, particularly in London (over £100 per pupil). Primary schools pay much less (around £50 per pupil) and special schools much more (over £250 per pupil). Regions such as London, the Northeast and Yorkshire & Humber pay more than some other regions. Generally, there is little consistent difference between the spend of academies and LA maintained schools, nor between rural and urban schools.

Diagram 1: Median per pupil energy spend in Secondary Schools - broken down by region and school type (2017-18)

How schools buy energy

Schools often look to outsource procurement expertise on energy through a broker or reverting to an external process which they regard as being robust. Even Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs), more likely to have their own procurement capacity and capability, were not found to be running their own energy procurement processes. This may be because the school needs not just a procurement expert, but one who fully understand the energy market, which is too specialist a role to fit in within schools’ typical staffing structures.

The most common routes to market were through a private broker, a local authority or a LA established company; some schools instead use a Public Sector Buying Organisation. Schools generally reported finding buying energy relatively easy, particularly when using a broker or local authority route, although many were not sure they had a good deal there were concerns that the incentives of brokers or LAs may not always match those of the schools (what academics call principal-agent differences).

Energy companies can try to pressurise schools into signing contracts quickly, as this quotation from an interviewee in a MAT demonstrates:

It’s a very high-pressure environment for a business manager. So, for example Gazprom with my 6th form college is just rolling over at the moment there’s no particular agreement in place. They e mailed me just the other day saying oh we’d be interested in chatting, so I just e-mailed back saying yeah that’s great - end of Covid we will start to look at this as I want to ensure I’m getting the best deal … we’ll be in contact. The next thing you know I’ve got a flurry of e mails from Gazprom saying that’s great, what we’ll do is get the deal together, we need it signed by the end of the day because we’re live pricing, so you need to sign the same day. I get a follow up the same day saying have I thought about it, are you ready to sign?... That is what business managers are dealing with from these energy companies.

(Participant 5 – Multi Academy Trust).

Reducing energy use

The relatively high variation in energy costs per pupil between schools is partly due to tariff differences and partly due to differing levels of energy use. High costs could be due to the age of the building, its state of repair, the energy efficiency of its infrastructure, or the behaviours of staff and pupils. There are a range of measures a school could put in place to reduce its energy costs.

All schools in the project had undertaken some kind of activity in recent years and the most common were the use of LED lighting, solar panels, and replacement boilers.

What can be done?

There are several ways schools could be supported to lower energy costs. The National School Buying Service could provide support walking a school through the energy procurement process and advise them throughout the journey. Schools who represent an outlier on energy spend could be supported to understand and take action on the underlying reasons for their high costs in terms of the efficiency of their energy infrastructure, their current energy deal or behaviours in school. Since the dissertation was written this service has started helping schools with energy procurements.

Government could consider intervening in the energy market with regulation to require energy providers to provide more transparent pricing to schools so that they are clear on what their future liabilities will be, or to make it very simple for schools to switch supplier quickly if they are not convinced they are accessing value.

There may be potential to develop a national aggregated energy deal if it delivers return on investment after factors such as support with meters and bill validation is factored in and if assurance can be gathered that the new deal would involve less cost to schools than the least costly energy deals currently in place.

Conclusions

There is potential to help schools save money by improving market regulation and procurement support, and individual schools can take steps to reduce significantly their energy use.

About the project

This research was a Master’s dissertation as part of the MSc in Public Management and Leadership, completed by Courtney Brightwell, supervised by Dr Peter Watts. The programme was funded by the DfE and Manchester City Council. Courtney can be contacted at brightwellcj@live.co.uk.