- by Kate Robertshaw, Undergraduate Research Scholar 2019 [1]

Not long after the University of Birmingham was established in 1900, Professor Hopkinson proposed setting up an archaeology museum in a letter to the Faculty of Arts Committee dated 1901.[2]

Subsequently, he was granted a sabbatical on the 4th March 1902 to travel to Greece for research.[3] When in Greece, Prof. Hopkinson travelled to Rhodes and purchased a selection of Greek pottery. Although we are unsure of Hopkinson’s exact reason for travelling to Rhodes, he states in a letter:

“[…] the best hope of increasing the Greek classes seem to be in appealing for interest to the historical imagination of students and not merely to their literary sense […].”[4] (Prof. Hopkinson to the Faculty of Arts Committee, 16th November 1902).

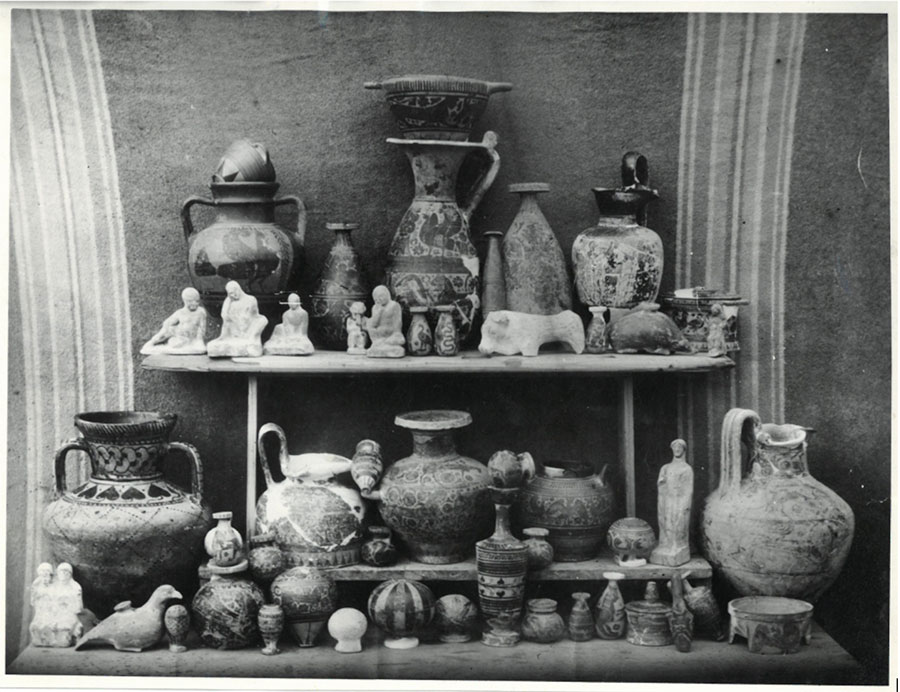

Thus, it seems that Prof. Hopkinson intended to create a teaching collection with his purchases. The archive of the Archaeology Collection has three photographs (Figures 1, 2, and 3) of groups of vases. Included in these photographs were the vases that Professor Hopkinson purchased for the collection. We do not know the context of these photographs and can only assume that they were taken in Rhodes when Professor Hopkinson was making the purchase. The vases Prof. Hopkinson purchased formed the nucleus of the Archaeology Collection, and his choice of objects suggests that he wanted representative types from various periods of Greek history.

Figure 1: various artefacts, including some later purchase by Prof. Hopkinson, potentially taken in Rhodes.[5]

Figure 2: various artefacts, some of which were purchased by Prof. Hopkinson, possibly in Rhodes.[6]

Figure 3: various artefacts, some later purchased by Prof. Hopkinson, possibly in Rhodes.[7]

The next major addition to the collection came with the gift of an Egyptian coffin lid, which was donated to the collection in 1904 by Professor John Garstang.[8] The collection received further Egyptian artefacts in 1939 through a bequest from the estate of Sir Robert Ludwig Mond.[9] It was after Mond’s death in 1938 that the artefacts in his personal collection were sent to the Trustees of the British Museum to be distributed among museums that were interested in obtaining them. In a letter between the Vice-Chancellor at Birmingham, Raymond Priestly, and Reader in Ancient History and Archaeology Professor R.P. Austin,[10] it was decided that the latter would travel to London along with Dr Bonser of the Archaeology Department in June 1939 to apply on the university’s behalf for some of the artefacts.[11] Both men met with the Trustees on 7th July 1939 and selected a variety of Egyptian objects from the collection which were then gifted to the University of Birmingham.

During World War II it seems that the Archaeology Collection saw a period of inactivity. We next have evidence of further acquisitions in January 1952, when the collection received a loan of various Greek and Egyptian artefacts from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. From the records connected to the loan, these objects were intended to be used in teaching and the loan was subsequently renewed in 1967 and again in 1988. At the beginning of the 1960s, the coffin lid donated by Prof Garstang unexpectedly disappeared from the collection. According to a memorandum composed by the Head of Department Professor Richard Allan Tomlinson thirty years later, it is believed that the coffin lid was donated to Leamington Spa Museum & Art Gallery by Dr Dudley and Dr Dorey of the Latin Department.[12]

The 1970s was quite a busy decade for the Archaeology Collection with several donations being made. First of these were a series of prehistoric Greek pottery sherds collected during excavations in the Aegean and donated by Lady Helen Waterhouse.[13] The Archaeology Collection also received artefacts from Professor of Geography Harry Thorpe.[14] A substantial number of objects were collected during his research trips from various locations in Somerset, and included a group of Roman coins, Neolithic arrowheads, and bronze rings. Finally, 129 obsidian and chert lithics originating from various regions in Pakistan were donated by the Wirth Family. These objects were collected by Mrs G.E. Wirth and her husband within a three-month period some time during the 1950s when Mr Wirth was managing a factory in Rohri, a city in the Sind region of Pakistan.

The Archaeology Collection continued to grow apace and received further donations of Near Eastern artefacts in 1981. Mrs M. Stevens gifted a group of objects including several clay bricks stamped with a cuneiform text, a couple of clay spindle whorls, and some obsidian scrapers. We know from correspondences between her and Professor Lambert[15] that these objects came from various regions in Mesopotamia and thus they were “ideal as typical specimens to illustrate materials from books and to assist with the general work of the department”.[16] Professor Lambert concluded from analysing the cuneiform inscriptions that at least a handful of the objects originated from the early Mesopotamian city of Ur. Another gift of an inscribed clay cuneiform brick with some bitumen attached was made to the collection in May 1981 by Mr M.W. Barker. He had come into possession of this artefact after his late father brought it home with him after serving in Iraq during World War I. Professor Lambert wrote in a later to Mr Barker that the brick and its inscription were Sumerian and dated to the Ur III Dynasty (c.2047-2038 BCE). Finally, during 1989 the Archaeology Collection received an added boost of a long-term loan of objects from the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.[17] This loan comprised of a diverse range of artefacts from Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, which enriched and expanded the number of cultures represented in the collection.

Returning to the coffin lid donated to the collection in 1902, we have little evidence regarding its whereabouts from the 1960s to the early 1990s.[18] It remerges in documentation in a memorandum by Professor Tomlinson in 1990 who began the long process of attempting to prove the Department’s rightful ownership of the artefact as the one donated to Leamington Spa in the 1960s. [19] The letter written by Prof Hopkinson to Prof Garstang in 1904 proved that the Archaeology Collection had at one point possessed a coffin lid. However, there was a lack of evidence to confirm that the coffin lid at Leamington Spa was the one that Garstang originally donated.[20] After a decade of negotiations, and despite no resolution to the ownership dispute between the University and the Museum at Leamington Spa, the University successfully secured a long-term loan from Leamington Spa, and the coffin lid was sent to the Archaeology Collection. Since its return to the Department, the coffin lid underwent conservation work in 2002 thanks to a financial grant from the West Midlands Regional Museums Council.

With the return of the coffin lid, it was decided in the early 2000s to create a new space with bespoke display cabinets in the Arts Building to house the collection. The purpose of this refurbishment was to increase the use of the collection and provide a space for teaching and outreach activities. In subsequent years, a number of small donations were made to the collection including a gift of Greek artefacts donated to the museum in 2006 by former Professor of Ancient History and Archaeology Richard Allan Tomlinson,[21] comprising vases from Magna Graecia along with Cypriot objects. Beginning in 2018, the collection received fresh attention with a redisplay of the objects based on themes that reflect the teaching and research interests in the Department.

The Archaeology Collection in the Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology has steadily grown since its inception in 1902. The donations made to the museum subsequent to Professor Hopkinson’s artefacts helped the Archaeology Collection grow to reflect the cultures and themes taught across the Department. Loans from the Ashmolean Museum and the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery supplemented the existing collection and helped introduce students to a wider range of material culture. The growth of the collection allowed for the museum’s refurbishment and incorporation of a dedicated teaching space. Today, the Archaeology Collection holds over 2,000 objects from Greek, Roman, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and European contexts. It is used actively in teaching and continuing Prof. Hopkinson’s initial plan for the collection, gives students the opportunity to learn directly from objects of the ancient world through taught seminars and volunteer placements.

[1] I would like to thank Anna Young, curator at Research and Cultural Collections (RCC), and Helen Fisher University Archivist at the Cadbury Research Library (CRL), for their assistance in the interpretation and sourcing of the original documents consulted for this report. My thanks also to Professor Simon Esmond Cleary, Dr Ken Wardle, Dr Gareth Sears, and Dr Gillian Shepherd for their insight into their personal experiences of the collection.

[2] Hopkinson, J. 1901. Minutes of the Faculty of Arts Committee Volume 1. Cadbury Research Library. UB/FAC1/A/1/1. 117/234-5. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[3] 1902. Minutes of the Faculty of Arts Committee Volume 1. Cadbury Research Library. 79/153. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[4] Hopkinson, J. 1902. Minutes of the Faculty of Arts Committee Volume 1. Cadbury Research Library. 117/235. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[5] Unknown photographer, location, and date. Research and Cultural Collections archaeology collection archive. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[6] Unknown photographer, location, and date. Research and Cultural Collections archaeology collection archive. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[7] Unknown photographer, location, and date. Research and Cultural Collections archaeology collection archive. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[8] Prof. John Garstang had been Reader of Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, documents detailing his excavations at Beni-Hasan are held at the Sydney Jones Library, University of Liverpool.

[9] Sir Robert Mond was a celebrated Chemist who discovered carbonyl compounds. He had a passion for Egyptology and funded numerous expeditions to Egypt, and helped clear the sites of Theban tombs in 1902 along with renowned archaeologists like Percy Newberry and Howard Carter. Mond also served as treasurer of the Palestinian Exploration Fund and the British School of Archaeology in Palestine. He was knighted in 1932.

[10] R. P. Austin was a Reader in Ancient History and Archaeology at the University of Birmingham and seems to have worked with the collection, he is cited in Beazley, J.D. 1942. Attic Red-Figure Painters (Oxford), 412, relating to a red-figure pelike in the collection. Austin is also highly praised as a “skilled professional scholar” in E.R. Dodd’s 1977 autobiography Missing Persons (Oxford), 73. He was also influential in the early years of the Classics Department at the University of Reading, who set up a travel award in his honour. R. P. Austin died in 1943.

[11] Austin, R.P. 1939. Letter to Prof. R. Priestly, Cadbury Research Library. UB/VC/3/1/7/14. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[12] During its time at Leamington Spa Museum & Art Gallery, the coffin lid received a great amount of attention and adoration from visitors and was notably the only Egyptian artefact held at the museum. Despite this, after some years on display, it was sent to Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery to be kept in storage Millward, E. 2013. ‘Meet George: the curious history of an Egyptian Coffin Lid’ Current Archaeology [online] available at https://www.archaeology.co.uk/articles/news/meet-george-the-curious-history-of-an-egyptian-coffin-lid.htm [accessed 25 Sept. 2019].

[13] Before coming to the university in 1952 with her husband, Mr Ellis Waterhouse, who became director of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, she had studied and worked at the British School at Athens. Helen Waterhouse had been an active archaeologist and colleague in the Department for several years, and upon her retirement became an Honorary Fellow of Ancient History and Archaeology.

[14] Prof. Harry Thorpe came to the University of Birmingham in 1946 and was later promoted to Head of Geography in October 1971 after serving as Acting Head upon the leave of Professor Linton in October 1962 (UB/FAC10/A/1/1- Cadbury Research Library. University of Birmingham. Birmingham). He was later added to the Queen’s Birthday Honours list in 1976 (US137- Cadbury Research Library. Cadbury Research Library. University of Birmingham. Birmingham).

[15] Professor Wilfred G. Lambert had been Professor of Assyriology at Birmingham and was a distinguished academic responsible for the translation of a great many cuneiform texts for the British Museum (including the Cyrus Cylinder). (Geller, M.J. 2012. ‘Obituary: Wilfred George Lambert, MA (Cantab), FBA (1926-2011)’ British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 5-7.)

[16] Lambert, W. G. 16th January 1981. Letter to Mrs M. Stevens, Research and Cultural Collections archaeology collection archive. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[17] Symons, D. 1995. List of loans compiled at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Research and Cultural Collections archaeology collection archive. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[18] The coffin lid was later housed in storage at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery which is supposedly where it was rediscovered by the department (Tomlinson, R.A. 1990. Memorandum concerning the Egyptian coffin lid, Research and Cultural Collections archaeology collection archive. University of Birmingham. Birmingham)

[19] Tomlinson, R.A. 1990. Memorandum concerning the Egyptian coffin lid, Research and Cultural Collections archaeology collection archive. University of Birmingham. Birmingham.

[20] John Garstang wrote three publications, in 1903, 1904, and 1907, relating to his excavations at Beni-Hasan though none of them elaborate on the coffin lid gifted to Birmingham. The 1904 publication (Annales du Service des Antiquités de I’Égypte, vol 5) mentions a donation made to the University of Birmingham but neglects to mention the specific items donated.

[21] Professor Tomlinson had first come to Birmingham as Assistant lecturer of Ancient History and Archaeology in October 1958, later being promoted to Senior Lecturer in 1969, and then Professor in 1971.