A roundup of some of the work done by students and staff using the University’s special collections in 2025.

Tracing Alma Tadema

As part of her Egyptology MA at Leiden University in The Netherlands, Gemma Blanch Soriano visited Cadbury Research Library (CRL) to better understand how the artist Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema (1836-1912) created his Egyptian-themed pictures.

Gemma Blanch Soriano, MA Egyptology, Leiden University.

"My MA thesis explores how Ancient Egypt was received in the Netherlands and Spain in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including via the art of Alma Tadema. The CRL has photographs of ancient Egyptian artefacts and ruins taken by or for Alma Tadema, and his sketches and tracings from museum collections and early Egyptological publications.

"Wonderfully, consulting the portfolios enabled me to relate Alma Tadema’s preparatory drawings to illustrations in Sir John Gardner Wilkinson’s three volume Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians (1837), which the CRL also has copies of, and, excitingly, to artefacts in the Leiden Collection at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (RMO).

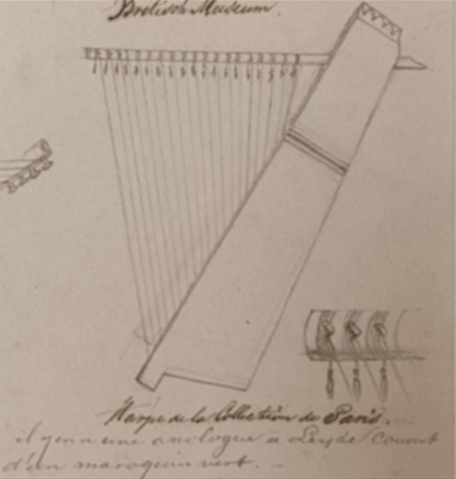

"Seeing CRL’s portfolios also allowed me to study the notes (in Dutch or French) that Alma Tadema wrote on his drawings. An interesting one is his ‘Green Harp’. Looking at the drawing (below) and the green harp one of the musicians plays in Alma Tadema’s painting Past Times in Ancient Egypt 3000 years ago (1863), we see that the two harps are the same. Moreover, the caption Alma Tadema added to the drawing reveals its connection to a harp on display at Leiden’s RMO.

The Green Harp, with Alma Tadema’s caption, which reads ‘Il y en a une analogue à Leyde couvert d'un maroquin vert’ [There is one similar in Leiden covered with green morocco leather]. Reference: AT/1/portfolio35/E1395]

"Using CRL’s Alma Tadema archive confirmed that this painter’s preparation went beyond the artistic sphere; that he included his Egyptological knowledge of the use and manufacture of the artefacts he drew and painted; and that he was well informed about the Leiden Collection. It is furthermore a great example of how an individual’s sources and creative output can be illuminated by the complementary use of archives, rare books and museum objects."

Back to top.

Meeting medieval manuscripts

The archives, manuscripts and rare books at the Cadbury Research Library (CRL) are often the raw materials underpinning exciting new research and dynamic student assignments. But, for Lucy Snow during her MA English Literature (2024-2025), the CRL’s manuscripts played their part in offering her the opportunity to help redesign the Meeting Medieval Manuscripts module, and thereby to make her mark on the university’s other crucial function, teaching and learning.

Lucy Snow (MA English Literature, 2024-2025)

"My Collaborative Research Internship tasked me with thinking about how CRL’s manuscripts might be used to introduce students to palaeography, transcription and how to handle medieval manuscripts. To that end, my first job was to familiarise myself with CRL’s holdings. From sermons to Books of Hours, the range of CRL’s manuscripts was wonderful to behold. Each manuscript has its own distinguishing features and signs of use, and it was fascinating to see how different generations of readers had engaged with the same text in different ways.

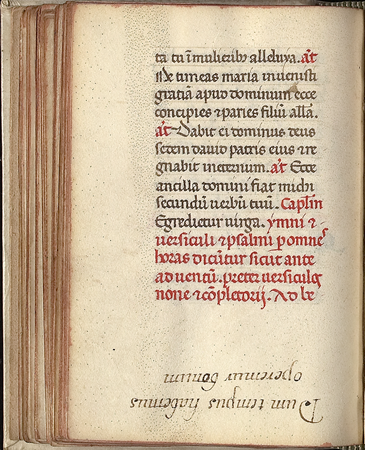

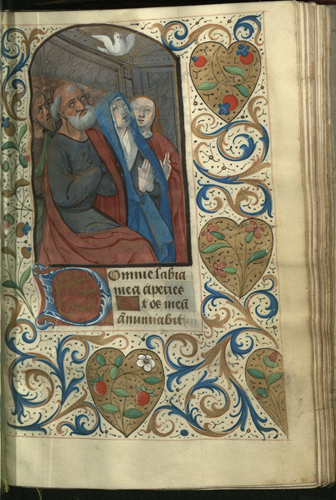

"The most richly illuminated manuscripts are my personal favourites. MS878 is a Book of Hours (c. 1500) with eighteen full-page illuminations depicting Biblical scenes, with vines and flowers twirling through the margins. In MS440, a fifteenth-century Book of Hours, an unknown hand has added a note in the margin, stating, in Latin, that ‘while we have time, let us do good’. Written hundreds of years ago, this thought still resonates, making me feel connected with this particular previous owner.

Marginalia at the foot of the page, which reads ‘Dum tempus habernus operemur bonum’ [While we have time, let us do good]. Reference: MS440.

One of the illuminations, with decorative border, in MS878.

"The CRL’s staff made me feel incredibly welcome. They helped me pinpoint resources and recommended some of their early printed books, which enriched my understanding of how manuscript practice endured after the proliferation of print. Taking part in this project—in collaboration with Dr Emily Wingfield, Dr Liv Robinson and Cadbury—resulted in me making recommendations on how the module could use the CRL’s manuscripts to teach and assess students. And I developed skills I will use during my PhD."

You can find entries for more medieval European manuscripts held by Cadbury Research Library by looking at our List of medieval manuscripts.

Back to top.

Rosalind Janssen: rediscovering myself

"It’s not every day that you find yourself in the archives. But that is exactly what happened to me when I was going through all forty-seven MS47 boxes, which comprise the papers of the Bible Churchmen’s Missionary Society (BCMS).

Rosalind is a PhD candidate at Lambeth Palace, an Honorary Lecturer at University College London (UCL) and a University of Birmingham alumnus (Ancient History and Archaeology, 1973)

"The BCMS archive is a core component in my PhD project for the Archbishop’s Examination in Theology at Lambeth Palace. Together with oral histories, I am probing BCMS’s theological training college for women in terms of gender and power relations.

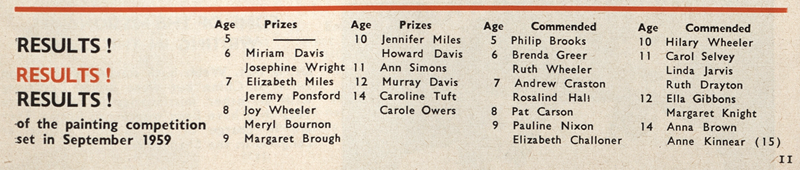

"Flicking through the BCMS children’s magazine Other Sheep, I discovered that, back in September 1959, I had entered a painting competition and been commended in its first issue from 1960. Not only did I find my seven-year-old self, but I also located the name of my six-year-old primary school friend Miriam. She and two of her brothers had all won prizes. When I shared my discovery with the archivist on duty that day, we were both emotional. The archivist told me: ‘This is what makes my job worthwhile’. I am so grateful for that shared moment and for her beautiful words.

Page 11 of the January-February 1960 issue of Other Sheep. Here the author, Rosalind (now Janssen, then Hall) is being commended for her artwork, and her friend, Miriam (aged 6), and her two brothers (Howard and Murray), are listed as prize winners. Reference: MS47/A/3/1/5/1/12.

"And, yes, Miriam is still my friend, but we no longer paint. Because her parents were BCMS missionaries in China, I have been sharing other findings with her over the course of my research. This project is therefore very much a living history, and all thanks are due to the wonderful archivists at the Cadbury Research Library who have been such a vital part of my journey of (re)discovery."

Back to top.

John Baskerville: 250

2025 marked 250 years since the death of one of Britain’s finest printers, Birmingham-based John Baskerville.

Copy from a portrait in The Roman and Italic of John Baskerville: A Critical Note, 1927. Classmark: p Z232. B2R6

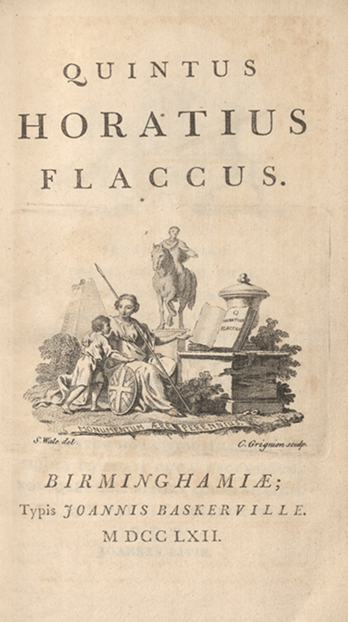

Baskerville’s typefont is his major legacy. While his peers filled the page with borders and ornamentation, Baskerville’s crisp and elegant fonts and his use of space produced books which were novel in their refined sobriety and restraint.

Title-page to Baskerville’s Horace, 1762. Classmark: Baskerville 59.

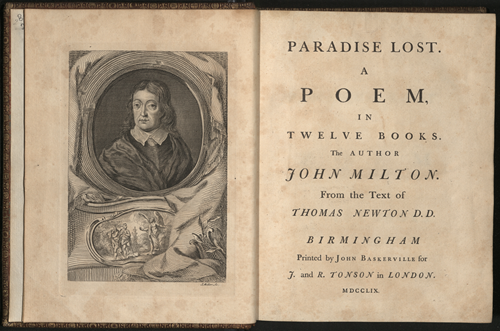

Baskerville enjoyed great success, notably through his editions of Virgil (1757) and Milton (1759). His friends, admirers and patrons included inventor and engineer, Matthew Boulton, whose copy of Baskerville’s beautiful Cambridge Bible (1763) is held at Cadbury Research Library, and the American Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin.

Frontispiece and title-page of Milton’s Paradise Lost, 1760. Preferring simplicity over ornament, the frontispiece is not Baskerville’s but was added by the publishers, the Tonsons. Classmarks: Baskerville 28; Baskerville 29. (2 copies.)

Also admired across Europe, Baskerville’s typefonts were bought after his death for the purpose of printing Voltaire’s 85-volume Complete Works, while the Italian writer, Vittorio Alfieri, commissioned the use of the types for his own works. Revolutionary France’s national journal, the Gazette Nationale, was set using Baskerville.

Baskerville’s font inspired other innovative print designers, such as Giambattista Bodoni (1740–1813), whose work also features as one of CRL’s named collections, and Bruce Rogers (1870-1957). And Baskerville’s font is still in use today, not just as a selectable font in Word, but the University of Birmingham’s own logo.

If you’d like to know more about Baskerville and some of the Baskerville books we hold, visit our online exhibition John Baskerville: 250 Years, refer to our Baskerville named collection page or search our FindIt@Bham library catalogue.

Back to top.

More information

We at Special Collections welcome all visitors and enquiries. More information about Special Collections’ three sites: Cadbury Research Library, Barber Fine Art Library, and Shakespeare Institute Library.