Migration – A Personal Story

Steve Gulati reflects on his and his family's experiences as first and second generation migrants, and also the contribution of migrant workers in the NHS.

Steve Gulati reflects on his and his family's experiences as first and second generation migrants, and also the contribution of migrant workers in the NHS.

Steve Gulati

The following piece was first produced in December 2020 as part of International Migrant’s Day. At the launch of Black History Month for 2022, in this the 50th anniversary of HSMC, we are republishing the blog to highlight the contribution that people of all ethnicities make to the NHS – and to academia. Steve Gulati will be publishing a further piece later this month which will focus specifically on the sometimes contested area of leadership development for minority ethnic groups in the NHS.

A Personal Story

The power of storytelling is increasingly recognised, and the first part of this piece will look at migration from an intensely personal perspective – the migrant story of my own family.

I am the son of immigrants. My parents came to England from India in the 1960s, a path trodden by many, many others from the newly independent countries of the former British Empire. My father arrived in London in November 1963, a cold month as he recalled, with three pounds in his pocket and three addresses to try for lodgings – one in London, one in Bradford and the other in Dundee. The addresses were important, as they were places owned by landlords who were known to be welcoming to immigrants – seeking and securing accommodation for a newly arrived migrant was certainly not straightforward for what was then termed a ‘coloured’ person. He found accommodation in London, but then came the first hurdle he faced – not in finding work (employment was relatively plentiful then), but finding work on the basis of what he had been promised, something I will return to below.

Migration occurs on many levels and for many reasons. In some ways, my father’s entire life was shaped by migration, forced and elective; as a child, he was part of the Punjabi population violently torn asunder and displaced by partition, an experience that arguably shaped his whole life given the suffering and atrocities that he witnessed as his family moved from what had newly become Pakistan to their native India. A schoolteacher in India, he met and married my mother, who was a headmistress in a neighbouring school – they were a very unusual couple in late 1950s India, a ‘love marriage’ rather than an arranged marriage – and soon afterwards, they ‘internally migrated’ from Punjab to the Andaman Islands, over 1700 miles away. And it was from there that they saw an advertisement in a local newspaper, asking for teachers from the former colonies to come to England to teach. Migration again, and this time to a different continent.

As an aside, I often asked my parents why they came to England given that they had a relatively comfortable life in India; their answer was always slightly confused, it was an adventure for a professional young couple they said, and they fully intended to teach in England for a few years and then return home. I was later to find that this intention to return is a common feature of many migration stories.

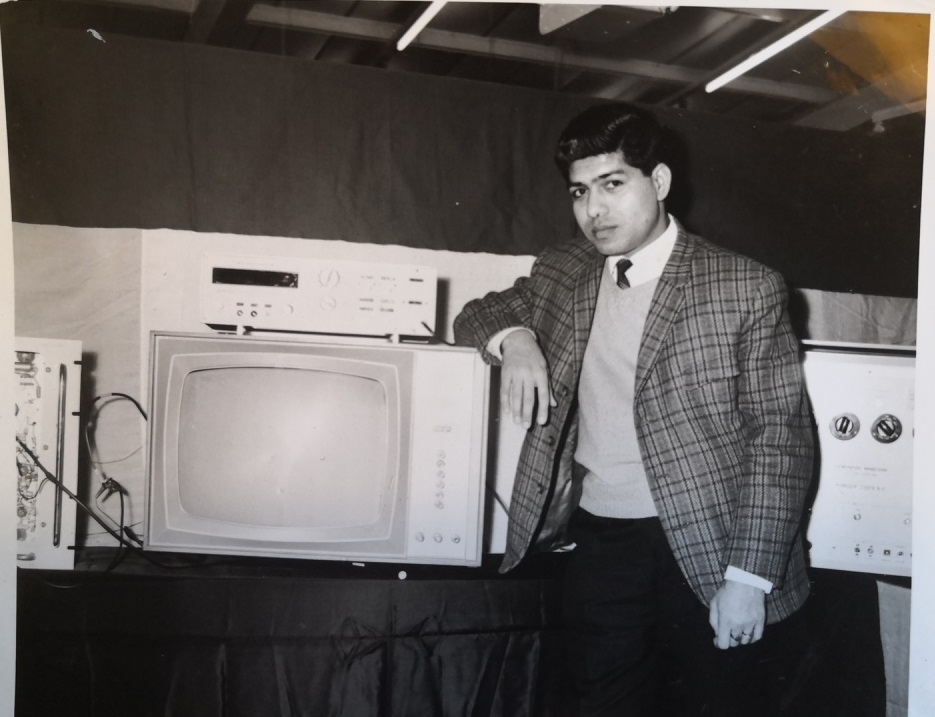

Whatever expectations they may have had, the reality in England was different. My father was devastated to learn that his teaching qualification from the University of Punjab was not acceptable to the English teaching authorities at the time – something not pointed out to him when applying to come to England – and he quickly had to find alternative work. His first job was washing dishes in a London restaurant, and he then found work in a local electronics factory. My mother joined him in England in 1965, and for her the culture shock was just as significant, her professional status as a Head Teacher utterly lost in 1960s London. It was around that time that my sister and I were born, and my mother devoted her time and energy to creating a loving and developmental home.

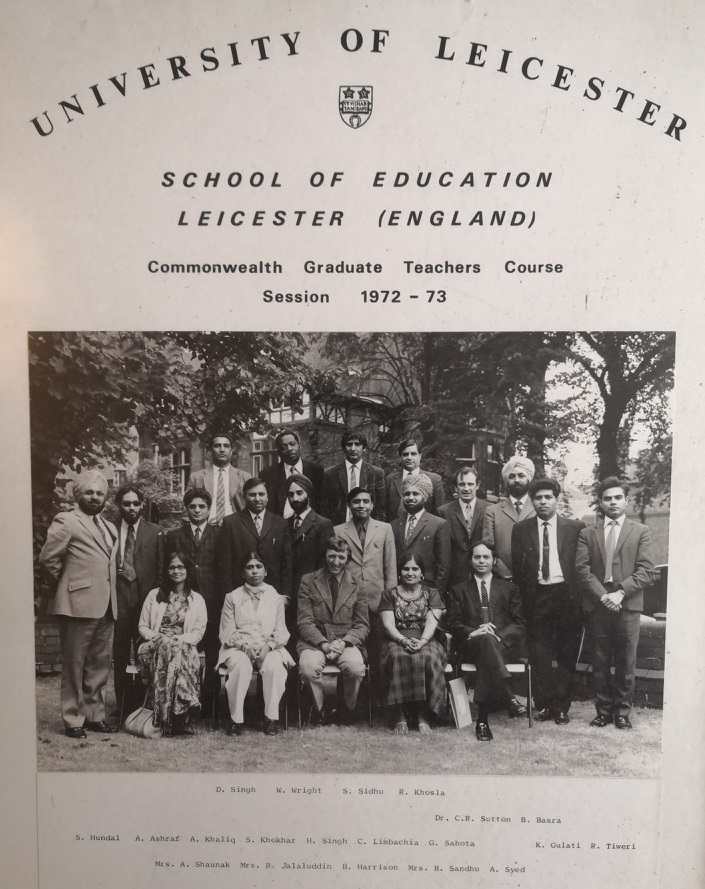

My parents were determined, though, to fulfil their dream of teaching in England, for by then it had become almost a point of principle. The fellow workers at my father’s factory were appalled at what they saw as a waste of talent, and it was through the union education officer there that my father learned of a Commonwealth Graduate Teachers Course at the University of Leicester, a conversion course which would allow him to teach in England. There followed fraught discussions between my parents about who should take up the course (both were eligible as qualified teachers in their ‘home’ country), but eventually they settled on my father taking up the opportunity. Arguably, another mini-migration – my father spent a lot of time in Leicester, while the rest of the family (initially, at least) stayed in London. My father qualified, and secured a post teaching at the school in Leicester where he had done his placement, and there he stayed for 25 years until retirement. My father died in 2014 and my mother in 2016, their ‘migration story’ completed. The story of public service continues, though; my sister is a teacher (also in Leicester) and I worked in the NHS for two decades before joining the University of Birmingham. So, this story of immigration is, like so many others, one of contribution and service to British society, an aggregate of 60 years’ worth and counting of public service, from my family alone.

The Migrant Contribution – a Continuing Story

The second part of this reflection considers the ongoing contribution of migrants to British public services, focussing on the NHS. The NHS has, since its inception, drawn heavily on overseas workers, and figures from the Government from June 2020 indicate that “around 170,000 out of 1.28 million staff report a non-British nationality. This is 13.8% of all staff for whom a nationality is known…between them, these staff hold 200 different non-British nationalities…over 67,000 are nationals of other EU countries – 5.5% of NHS staff in England”. I have written before about migration and the NHS, and reflecting on International Migrants Day prompted memories of my direct experience of recruiting, integrating and working alongside more recent migrant talent in the NHS.

I was involved in the overseas recruitment of nurses to NHS Trusts in London and the Midlands from the late 1990s for around ten years, sourcing staff from India (the irony was not lost on me!), South Africa and the Philippines. The actual process of recruitment and selection was instructive, and at times sobering – the intensity of the desire to come to the UK to work in the NHS was strongly evident, even overwhelming to the candidates at times, and as selectors we were all too aware that for many of the applicants, success in obtaining a post in the NHS could be financially transformative for their families through remittances. Candidate knowledge of the NHS, its founding principles, the range of services, the challenges, and of the values was in many cases greater than that of UK born applicants. The contribution that these staff made when eventually joining the NHS was immense: working arduous, unpopular or difficult to fill shift patterns, forming effective working relationships with remarkable speed, bringing new perspectives to patient pathways, showing empathy and compassion when they might have themselves felt lonely at times, and working hard also at adjusting to a culture often very different to their own. It was humbling to witness, and many of my second generation migrant colleagues commented that what we saw from this new migrant workforce put the efforts and sacrifices of our parents into sharp focus.

My involvement was solely around nurse recruitment, across a range of specialties – general nursing, operating theatres, ITU, trauma and orthopaedics – and the hospitals in which I worked spent a great deal of time and resources in ensuring that the induction and integration process was carefully attended to. This was encouraging, indicating an even-handed approach to assisting both the migrant workforce and also the teams within which they would be located; carefully constructed induction programmes for the migrant workers were run simultaneously to cultural awareness schemes for the host teams. This was, therefore, very much an enlightened approach, operationally at least, to the sourcing and deployment of migrant labour and skills – but at a strategic level, it was not without issues.

Ethical Issues

One of the striking features of recruiting migrant workers to the NHS was the nature of the discussions around ethics. This was, undoubtedly, patchy – some NHS Trust leaders were focussed purely on staffing numbers and ratios, but others had Board level discussions about the ethical dimension of overseas recruitment. The issue has attracted scholarly interest, and at a practice level there were serious concerns about the depopulating of overseas resources, the impact on individual migrant workers of dislocation, and of perceptions of the impact on opportunities for the indigenous workforce. In my own experience as a Board member, at least, these discussions did not feel as though they were located in racism or exclusion, neither in an explicit nor coded manner, but it was noteworthy how the debate often boiled down to economic or service delivery necessity: “we need them, and they want to come”. Connecting this back to the experience of my own family, I knew that the issue was somewhat more nuanced than that, and it was interesting to note how little the discourse had changed from the economic imperative.

Migrant Workers & Covid-19

The coronavirus crisis that has swept the globe in 2020 has many perspectives and many stories to tell. One of these is the impact and importance of the contribution that migrant workers have made to the UK society and economy during the pandemic. This has a wide lens, and the contribution by migrant workers at all levels contributing to the continuing effectiveness of the NHS just one of those perspectives. Issues of visas and ‘surcharges’ for migrant workers, for example, have penetrated public consciousness as never before in the UK, and perhaps in the medium to long term the experience of the pandemic could help to reframe debates about migration and population flows.

A story worth telling

So this year, perhaps more than any other, International Migrants Day is a time to consider our attitudes and approaches to migration, both at a personal and at a policy level. The pandemic makes vulnerable people, including some migrants, more vulnerable than ever; equally, the migrant contribution to the economies and societies of wealthy nations is more pronounced and more visible than ever (if we choose to see it). I have used this space to tell my story, but it is not an unusual or extraordinary tale – quite the opposite, it is replicated many tens of thousands of times across the UK, and it still continues to this day. And it is, perhaps, for that reason that it is worth telling.

At the launch of Black History Month for 2022, in this the 50th anniversary of HSMC, we are republishing the blog to highlight the contribution that people of all ethnicities make to the NHS – and to academia.