Pulse oximetry screening is a safe, painless and simple test that has been shown, in research studies involving almost half a million babies, to identify consistently babies with life-threatening heart defects (critical congenital heart defects or CCHD) before they become seriously unwell.

Pulse oximetry screening is a safe, painless and simple test that has been shown, in research studies involving almost half a million babies, to identify consistently babies with life-threatening heart defects (critical congenital heart defects or CCHD) before they become seriously unwell.

Pulse oximetry screening research

In 2007 Professor Andrew Ewer’s team from the University of Birmingham published the first systematic review of all the available studies on newborn pulse oximetry screening (POS). They concluded that we needed more evidence on the accuracy of the test from larger, high quality studies. Following on from there, Professor Ewer’s team undertook the UK PulseOx study which was published in the Lancet in 2011 and Health Technology Assessment in 2012 which showed that adding pulse oximetry to existing screening methods increased detection of CCHD from 50-70% to 92%.

In 2012 they published a further systematic review in the Lancet (which included over 230,000 screened babies) that showed that POS met the criteria for routine newborn screening.

Since then there have been further studies showing similar results and Professor Ewer’s third systematic review in the Cochrane library which include over 450,000 screened babies confirmed their previous findings. In 2017 a team from the USA showed (in a population of over 27 million babies) that pulse oximetry screening unequivocally reduced mortality in newborn babies with CCHD by one third.

As a result, an increasing number of countries have recommended routine pulse oximetry screening for all newborn babies and in 2024, the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) produced the first National Framework for Practice for pulse oximetry testing.

Background to UK POS uptake

In the UK, in 2010 only 7% of all hospitals routinely screened newborns with POS. This increased to 18% in 2012 and to 40% in 2017.

In 2019, following a successful pilot study, the UK National Screening Committee (NSC) undertook a second public consultation on the introduction of POS. Despite overwhelming support from parents, patients, baby heart charities and doctors and nurses caring for newborn babies, the NSC decided not to recommend POS. Full details of the public consultation can be found here.

Following on from this decision, a survey in late 2020 shown uptake of POS had increased to 51% of hospitals and also reported an increase in interest in starting POS in the majority of the remaining hospitals.

In 2023, POS uptake in the UK had increased from 51% to 78% and POS had been recommended in both the National Neonatal Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) report (2022) and the NHS Race and Health Observatory report (2023).

Following this the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) called for equity of care for all UK newborns with respect to POS provision and in 2024 produced a Framework for Practice for pulse oximetry testing which has become the national standard (see also: Routine pulse oximetry testing for newborn babies: a framework for practice).

International uptake of pulse oximetry screening

An increasing number of countries now recommending universal newborn pulse oximetry screening. These countries include:

USA, Canada, New Zealand, China, Spain, Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, Poland, Germany, Austria, Nordic Countries (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Iceland, Denmark), Ireland, South and Central American countries, Sri Lanka, Israel, Kuwait and Abu Dhabi.

The National Screening Committee's public consultation

The UK’s National Screening Committee has been considering routine pulse oximetry screening for critical heart defects in newborn babies for a number of years. In 2019 the National Screening Committee launched a public consultation on its decision not to offer pulse oximetry screening to all UK newborn babies.

Many parents, clinicians and charities responded. There were 173 responses including 69 from parents, 64 from clinicians (or clinical societies including British Association of Perinatal Medicine [BAPM], Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health [RCPCH], British Congenital Cardiac Association [BCCA], Neonatal Society, Paediatricians with a special interest in cardiology [PECSIG], Congenital Cardiac Nurses Association [CCNA] ), and five charities, Children’s Heart Federation, Tiny Tickers, Little Hearts Matter, British Heart Foundation and Children’s Heartbeat Trust.

Read all the responses at:

Following this consultation the NSC considered all the responses (see pages 26-29 and 40-52) and upheld their decision not to introduce POS stating that they felt more research was needed.

The National Screening Committee’s decision will affect every baby born in the UK (over 700,000 per year). They are currently asking for feedback about how well they listen to experts and members of the public when formulating their decisions.

Pulse Oximetry

What is pulse oximetry screening?

Pulse oximetry screening is a simple test performed on babies before discharge from hospital. It takes less than five minutes and is completely harmless and painless.

The test is carried out using a pulse oximeter, a special machine that is used routinely throughout the world to measure the amount of oxygen in the blood. A small probe is wrapped around the baby’s hand and foot and connected to a small, handheld machine that measures the baby’s oxygen levels by shining a light through the skin.

Research at the University of Birmingham and by others has shown that by measuring blood oxygen levels in newborn babies, it is possible to identify the small number of babies who have an unidentified critical heart defect; these babies usually appear healthy at birth but often have lower oxygen levels.

The pulse oximetry test identifies babies with lower oxygen levels so we can check these babies very carefully to identify a possible heart defect before the baby becomes unwell.

In the USA, where pulse oximetry screening is routine for all babies, a large study has clearly shown that death from critical heart defects was reduced by one third in babies offered the screening compared with those who were not offered it.

Currently less than half of the babies born in the UK are offered this test and over half will not. Whether or not a baby has the test depends on the hospital of birth. If the National Screening Committee were to recommend this test then all babies born in the UK would be screened.

Will my baby receive this test?

Whether your baby receives this test or not depends on where they are born. In a recent UK survey of hospitals that were not performing pulse oximetry screening, almost two-thirds are considering its introduction. Many are waiting for the National Screening Committee's decision before starting.

The charity Tiny Tickers recently introduced 'Tommy's campaign', which aims to provide pulse oximetry machines for those hospitals who would like to start pulse oximetry screening; machines have currently been provided in 35 hospitals.

Other children’s heart charities, including the Children’s Heart Federation and Little Hearts Matter, have also been running campaigns advocating pulse oximetry screening.

A number of countries, including the USA and several European countries, have already recommended pulse oximetry screening. Professor Ewer led a large influential group of European doctors who strongly advocated routine pulse oximetry screening across Europe.

Why has this test been introduced in some hospitals?

Pulse oximetry screening has been shown to identify babies with life-threatening heart defects (otherwise known as critical congenital heart defects or CCHDs) and reduce deaths from these conditions by one-third. Pulse oximetry also identifies other serious conditions, such as infections and breathing problems, which allows earlier treatment for these problems also.

There is strong evidence to suggest that pulse oximetry identifies babies with these conditions early before they deteriorate. Many doctors think that this is a test that can save lives and reduce the time to diagnosis resulting in earlier treatment.

This consultation is an opportunity for everyone, including doctors, nurses and parents, to express their views and experiences with this test.

What happens to babies who are currently screened with pulse oximetry?

UK research, including the National Screening Committee’s pulse oximetry pilot in 2015, has shown that what happens to babies who are screened is very consistent.

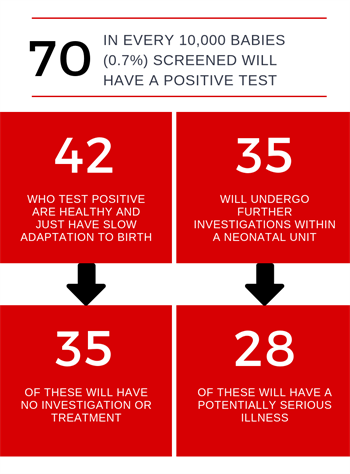

About seven in every 1,000 babies screened (0.7%) will have a positive test. More than half of the babies (six out of every 10 or 60%) who test positive are healthy and they just have slow adaptation to birth. Five out of these six babies will develop normal oxygen levels very quickly and will need no investigation or treatment.

About seven in every 1,000 babies screened (0.7%) will have a positive test. More than half of the babies (six out of every 10 or 60%) who test positive are healthy and they just have slow adaptation to birth. Five out of these six babies will develop normal oxygen levels very quickly and will need no investigation or treatment.

Five out of every 10 babies who test positive (3.5 out of every 1,000 babies tested) will undergo further investigations and almost all will be admitted to the Neonatal Unit for further assessment. Most babies will have blood tests, X-rays and other investigations to try to find out the cause of the low oxygen levels.

Of the babies admitted to a Neonatal Unit after a positive test*:

-

One in 10 will have a heart problem and they will benefit from early diagnosis and treatment

-

Seven in 10 will have a breathing problem or infection and most will benefit from the test by early diagnosis and treatment of a potentially serious illness

-

Two in every 10 babies will be healthy (less than one in every 1,000 babies screened) and will have had any unnecessary tests that may have resulted in a delayed discharge from the Neonatal Unit

So about eight out of 10 babies (80%) who are admitted to the Neonatal Unit after a positive test will have a condition that is considered to require treatment which will have been detected early. By using pulse oximetry screening, this early detection can improve a baby’s chances of survival and long-term quality of life.

In 2018, the National Screening Committee convened a work group of senior neonatologists and experts in public health in screening to decide on the balance between benefits and harms of pulse oximetry screening. They concluded that most babies who tested positive and were admitted to a Neonatal Unit will benefit.

*Analysis from the National Screening Committee’s pulse oximetry pilot (pages 110-111)

Why does the National Screening Committee not want to recommend pulse oximetry screening for all babies?

The National Screening Committee summarised its decision as follows:

‘…there is currently insufficient evidence to suggest that there is a greater benefit to babies with the inclusion of pulse oximetry than that afforded by the current screening programme alone. It is also noted that there are harms associated with screening and the further investigations following a positive screening result.’

This means that the National Screening Committee does not think that the evidence showing benefit of pulse oximetry screening is convincing.

What is the current screening programme for heart defects in newborn babies?

All babies are currently screened for heart defect while still in the womb (antenatal ultrasound) and following birth (postnatal clinical examination).

- Antenatal ultrasound – between 2014 and 2017 in the UK, less than half (42%) of babies with heart defects that require intervention were identified before birth (2018 NICOR report, table 12a). Between different health regions in the UK there is great variability in the rate of identification – between 33% in the lowest performing regions and 62% in the highest – so some hospitals are much better at this than others

- Postnatal examination – despite best efforts examination fails to identify about 45% of babies before collapse with critical congenital heart defects and up to 30% are sent home without diagnosis. Some of these babies will die and many will have a worse outcome as a result of late diagnosis. Research has consistently shown that when pulse oximetry is added to the existing programme the identification rate for critical congenital heart defects increases to between 90 and 95%

What does the National Screening Committee mean by ‘harms’?

- In any screening programme the benefits must outweigh the harms. So, the benefits such as earlier diagnosis and treatment and reduction in death rate must be balanced against the harms of the screening test

Harms raised by the National Screening Committee

Parental anxiety – It is possible that some parents will be anxious if their baby does not pass the test. This information sheet explains what happens during screening to reduce any possible anxieties. In the Birmingham research study parents of babies who tested false positive were not significantly more anxious than those whose babies passed the test. What is your opinion on this?

Longer stay in hospital – Babies who have a serious condition will need to stay in hospital until they are better. Most babies who do not pass the test and are healthy are correctly identified within an hour or two and are not admitted to the neonatal unit. This is a short delay which rarely affects the time of discharge. Babies who test positive and are healthy who are admitted to Neonatal Unit (less than one baby per 1,000 screened) are usually discharged within 12 hours*.

Transfer to Neonatal Unit – About half of the babies who test positive (3.5 per 1,000 screened) are admitted to the Neonatal Unit.

Overdiagnosis or overtreatment – This is a problematic area as some of the non-cardiac condition (such as breathing problems and infections) are difficult to diagnose with absolute certainty. In the UK pilot and in a study from the University of Birmingham, about 80% of babies admitted to Neonatal Unit had a diagnosis of a potentially serious condition.

The working group formed by the National Screening Committee to address the issue of overdiagnosis and overtreatment decided that in most (six out of eight) of these conditions there was a clear benefit to early diagnosis with pulse oximetry and in one the benefits outweighed the harms. Only one condition did not benefit and this accounted for only one baby in over 32,000 screened*.

False positives – These are the babies who do not pass the test but do not have the condition screened for. In the strictest sense, all babies who do not have a critical congenital heart defect are false positives. However, there is an advantage to identifying the other non-cardiac conditions (see above) and so many people consider only the completely healthy babies to be false positives.

False reassurance or false negatives – Like many screening tests, pulse oximetry is not a perfect test and will miss some babies with critical congenital heart defects. The proportion of babies missed is reduced to less than 10% if pulse oximetry is added to existing screening.

*Analysis from the National Screening Committee’s pulse oximetry pilot (pages 110-111)