World Autism Acceptance Day (WAAD), or World Autism Awareness Day, can present a dizzying assortment of schemes, projects and ideas from a plethora of associations, campaign groups and individuals. In fact WAAD has grown rapidly in scope and ambition since it was first adopted by the United Nations in 2007, with some organisations designating the whole of April as the month during which we should be ‘aware’ of autism. And who can fail to notice the current prominence in our TV schedules of ‘awareness raising’ programmes such as The A Word and Employable Me, to name but two autism-based outputs?

But all of this begs the question: what should we be ‘aware’ of, and what does ‘acceptance’ mean? Can these terms convey the complexity of the issues faced by autistic individuals and has WAAD become little more than an incoherent campaign adopted by disparate groups, sometimes with conflicting values, and with little real impact? Certainly, the statistics in the UK alone are far from encouraging: autistic individuals continue to face high levels of educational exclusion and impoverished longer term outcomes. As professor Nick Hodge pointed out in a recent interview on the Autism Centre for Education and Research (ACER) blog, the label of ‘autism’ itself can be problematic: in schools for example, ‘a pupil is no longer known by her or his name, but by a category.’

Wenn Lawson, in his profound and insightful book, Concepts of Normality, asserts that ‘inclusion means finding ways to work with difference.’ His notion of ‘diffability’, that autistic individuals think, operate and manifest their abilities in a different way from those who are non-autistic, or ‘neurotypical’, can be a helpful axis on which to centre what can often be contradictory and divergent presentations of autism in the broader media. To what extent is autism presented as a form of difference, to be respected, supported and celebrated, or is it portrayed as a collection of impairments which must be either repaired or ‘treated’ with therapeutic interventions?

Transforming Autism Education

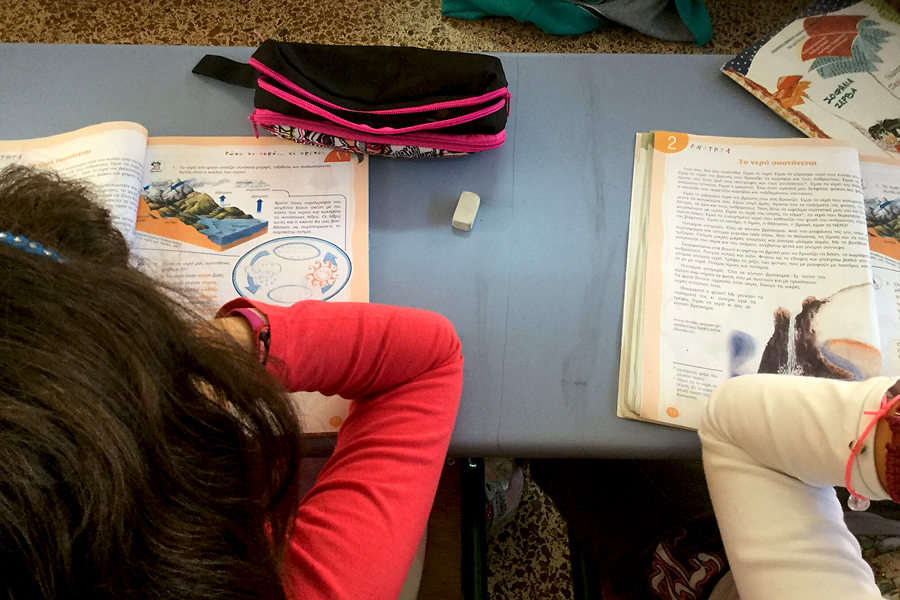

Members of the team at ACER are involved in a project called ‘Transforming Autism Education’ (TAE), an ambitious scheme which aims to set up teacher training programmes in Greece and Italy to facilitate the inclusion of primary school-aged autistic children. One of the key unifying models on which the project is based, and so enabling the numerous researchers and practitioners to find coherence across diverse European cultures, is the notion of autism as a form of difference, as providing part of the diversity of humankind. Using the Autism Education Trust training programmes as a founding template (which members of ACER were instrumental in developing in the first instance), participants learn about autism through ‘four areas of difference’, which must be understood, valued and accommodated. It is only by having this ‘awareness’ that education practitioners can begin to truly support and include autistic children in the classroom, in itself a necessary stepping-stone to acceptance in broader society.