In the run up to Christmas, six members of B-Film discuss their choices for films that help define the festive season.

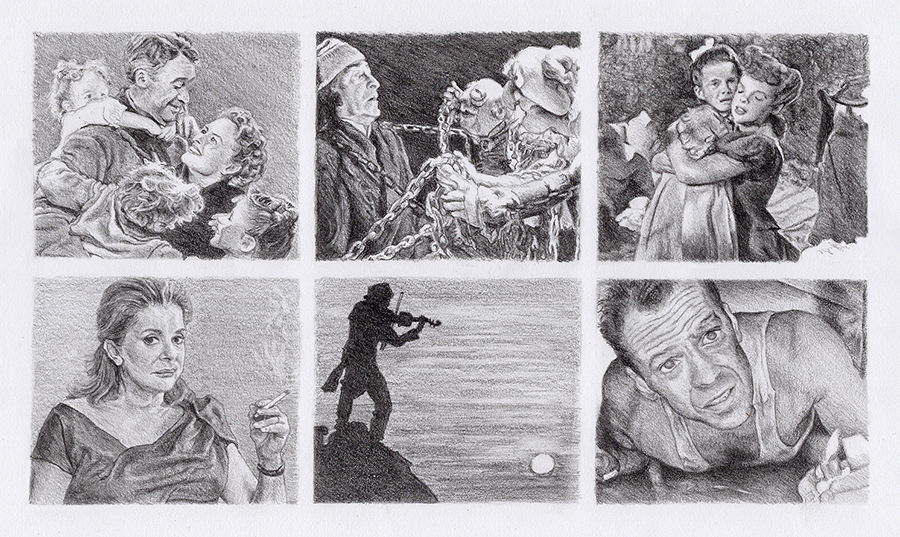

Two things finally convince George Bailey (James Stewart) in Frank Capra’s It's a Wonderful Life (1947) that he has returned from Pottersville to Bedford Falls: the blood he tastes on his cut lip and a collection of rose petals found in his pocket. Both are facts of Bedford Falls, now restored: the petals belong to his daughter Zuzu, and George was hit in the face shortly before his time in Pottersville. And both are small illustrations of pain: Zuzu’s protection of her rose inadvertently caused her illness, which George blamed on her teacher, which led to him being struck by the teacher’s husband. These visceral re-minders to George act as a reminder to the film’s audience: life, even at Christmas, can be painful. George’s story is built around moments of pain and, even now as he runs back to the Bailey family home, he believes he is facing jail. It all works out, as it has done before, but the film insists that its emotional high should be balanced against its emotional lows. Life can never be perfect. And so, in the end, this famous holiday fantasy finds the reality shared by anyone whose Christmas is an annual picture of glorious imperfection. Dr James Walters

Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol has spawned numerous adaptations for stage, screen, and radio. However, one would be hard-pressed to find a more heart-warming version than The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992) directed by Brian Henson, son of late Muppet creator Jim. On Christmas Eve, the miserly money-lender Ebenezer Scrooge (Michael Caine) is visited by three ghosts who prompt him to change his ways and embrace the true spirit of Christmas. Double Oscar-winner Caine proves an inspired choice as Scrooge, having told Henson that he would play the part as if there were ‘no puppets around me’. For the audience, though, the familiar cast of furry favourites is impossible to ignore. Kermit the Frog plays a suitably downtrodden Bob Cratchit, while Miss Piggy finally captures the heart of her frog prince as Bob’s wife Emily. Fozzie Bear turns his comedic talents to producing rubber chickens in the role of Scrooge’s former employer Fozziwig. And Sam the Eagle struggles to repress his American patriotism in a scene-stealing performance as a British schoolmaster. The cast is completed by Gonzo’s Charles Dickens, who assumes narratorial duties alongside Rizzo the Rat. With its dancing horses and singing vegetables, this is certainly not Christmas as Dickens envisaged it, but it is a uniquely Muppety one. Dr Andrew Watts

I hate Christmas, which is why I love Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). This MGM musical directed by Vincente Minnelli and starring Judy Garland is composed of a series of seasonal family scenes from summer 1903 to spring 1904. The film therefore literally hinges on Christmas, when the almost posh Smith family is shown coming to terms with the fact that all its members, including four daughters and a son, must move from the idyllically backward St. Louis to the terrifyingly modern New York. The film appears set for a sickly-sweet festive celebration, but Garland sings her big number ‘Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas’ as a mournful dirge in tune with her little sister Tootie’s dismay at being uprooted. Thus emboldened, the psychotic Tootie (played by 7-year old Margaret O’Brien) heads out to the garden where she has sculpted her parents and siblings in snow, and proceeds to hack, blast and smash apart her pure white kinsfolk in what is the most riotously disturbing attack on the family unit in American cinema. Patricide, matricide, fratricide; I’m on her side. Professor Rob Stone

Tragedy haunts the Vuillard family in Arnaud Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale (2008) in the guise of the childhood death from leukaemia of Abel and Junon’s first son Joseph, none of the three younger siblings having been able to supply compatible bone marrow. As adults the elder two, Elisabeth and Henri, detest one another, but the surprise diagno-sis of leukaemia in Junon is the occasion for a Christmas family gathering to which Henri is re-admitted after a ‘banishment’ insisted on by Elisabeth six years previously. When it turns out that only Henri and Elisabeth’s mentally ill son Paul can offer Junon compatible bone marrow, and it is unexpectedly revealed that youngest sibling Ivan’s wife Sylvia was passionately loved by family tag-along cousin Simon as well as by Ivan, Christmas turns out full of confrontation, cruel words and drunkenness (along with plenty of more traditional entertainment). The film may conform to the stereotype of French cinema as over-intense, but the great performances from Catherine Deneuve (Junon), Mathieu Amalric (Henri), Melvil Poupaud (Ivan), and Jean-Paul Roussillon as squat Abel, the only stabilizing force in a family of firecrackers, certainly make us ponder the ties that bring families together at Christmas, against all the odds. Dr Kate Ince

Little makes me feel more Jewish than Christmas, no wonder then that Fiddler on the Roof (1971) tops my list of favourite films for a seasonal stopping-in. It’s a multi-award-winning musical that has it all: history, pathos, and prescience; family feuds, knowing winks, memorable melodies and mass migration. Conjuring shtetl life in 1905 Imperial Russia, the story follows Tevye, a poor milkman, as he navigates the clash between old and new world values and acts, until the pogroms force the villagers to uproot for ‘Ameri-ca’. Typical of the musical genre, this clash is animated by romance: his older daughters’ love-borne rather than arranged marriages. And for further festive flavour if you need it, there’s a cast out woman, betrayal, a resurrection and a song about a donkey…well, ok a ‘horse-mule’. As well as Topol’s famed role as Tevye, Molly Picon, one of the world’s most important Yiddish performers, is the matchmaker, Yente. Michael Glaser, who would shortly be a household name as Starsky, is the Marxist revolutionary, and soon-to-be son-in-law, Perchik. Ruth Madoc (yes, of Hi-de-Hi! fame) is Fruma-Sarah, star of ‘Tevye’s dream sequence’, a wondrous number that remains for me the pinnacle of the film and even the genre itself. Dr Michele Aaron

For those like me, who prefer to keep Christmas a little bit at arm’s length, there can only be one logical choice for a seasonal celluloid sojourn. Admittedly, John McTiernan’s action classic Die Hard (1988) is, at best, only tenuously a ‘Christmas’ movie. By design, the film isn’t concerned with being serious or sentimental about the values and meanings of the season, it’s concerned with blowing stuff up. Part cops-and-robbers and part cowboys-and-Indians, the film follows New York City policeman John McClane, played by Bruce Willis (a role he reprised four more times in the following twenty-five years), as he hunts down uzi-toting terrorists who have interrupted and taken hostage his estranged wife’s office Christmas party. Action abounds and shenanigans ensue, until McClane and the terrorist leader Hans Gruber (portrayed by Alan Rickman with all of the trademark sneering sarcasm he brought to his screen villains) face-off, Western-style, in a final shoot-out. Initially released in July for the summer blockbuster market, Christmas features merely as a loose backdrop and handy source of props, music and one-liners. And that’s why it’s such a brilliant Christmas film. There’s neither need nor time to get teary-eyed with the contemplation of family or faith; just put your feet up, pick up a mince pie and strap yourself in for the ride. Yippee-ki-ay Christmas-lovers. Dr Richard Langley