The Great War saw battlefield injuries, infections and trauma on a scale never before witnessed. British doctors struggled not only with the high numbers of wounded troops arriving at military hospitals across the country, but with new conditions such as shell shock, ‘soldier’s heart’ and trench foot.

At the same time, medical staff were faced with a dearth of effective medicines, while medical equipment and practices such as X-rays were rudimentary and used infrequently. Medics were forced to think on their feet and even appeal to the local civilian population to grow medicinal herbs, as happened throughout Warwickshire.

‘One of the hardest myths to dispel is that war brings medical advancement,’ asserts Dr Jonathan Reinarz, Director of the History of Medicine Unit within the University’s School of Health and Population Sciences. ‘It certainly makes people more resourceful, and doctors learned a lot of lessons during World War One, especially those who would not have been given much responsibility in peacetime, such as students, but medical historians really challenge this idea that war brings about improvements in medicine.’

What war does do – and this was certainly the case in World War One – is provide informal research opportunities that contribute to post-conflict medical advancements. For example, doctors saw thousands of soldiers returning from the trenches blind, deaf, paralysed or unable to speak – yet without any physical injury to explain the symptoms. It wasn’t until 1915 that the first paper on ‘shell shock’ was written, by a medical officer called Charles Myers (although he didn’t invent the term).

‘When you are seeing the same kinds of cases repeatedly coming before you, you start to identify patterns,’ says Jonathan. ‘For instance, doctors were seeing a huge number of men with the symptoms of venereal disease (VD) and trauma that they hadn’t been taught about during their medical training. So they were learning about new conditions as they went along, and afterwards were able to use that information to take medical knowledge forward.’

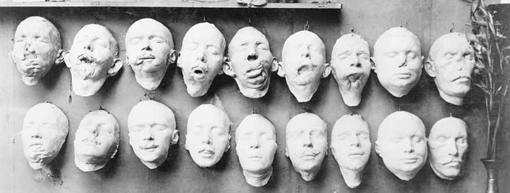

However, medical techniques still in their infancy at the turn of the 20th century, such as the system of triage, became standard practice in the Great War, while the time taken to treat soldiers was greatly reduced with the development of mobile medical equipment: mobile X-ray units were used to locate bullets and shrapnel, for example. Today’s maxillofacial surgery to repair facial fractures, using external fixation, was pioneered during World War One, although it took much longer to perfect.

Plastic surgery was also first performed during the Great War: a naval officer, Walter Yeo, who suffered terrible facial injuries during the naval Battle of Jutland, was given new eyelids with a ‘mask’ of skin grafted across his face and eyes in a procedure known as ‘tubed pedical’.

‘So modern medicine was starting to emerge during World War One, but it was still early days for procedures such as blood transfusions, and doctors still didn’t really understand shock and the treatment of burns,’ explains Jonathan. ‘People think of these as developments that came out of war, but the fact was that doctors were hard-pressed to deal with the sorts of injuries they were seeing.’

The terrain on which most of the Great War battles were fought – the soggy fields of northern France and Belgium and the insanitary trenches – resulted in long-term problems from wounds unlike those witnessed in, say, the Boer Wars.

‘Because the Boer Wars were fought in South Africa, where the climate was very different, there was less infection of bullet wounds than was the case in World War One, where the fighting took place in fields that had been fertilised and polluted with microbes over centuries, resulting in far more infected wounds. There wasn’t the easy healing that had been experienced in South Africa.’

But at the same time, doctors became better at cleaning wounds and cutting away dead and infected tissue before stitching them.

As well as the challenges of mass injuries and new medical conditions, doctors also had to cope with a health system that had been turned on its head by war. Only relatively well-equipped and well-staffed centres such as Birmingham were able to adapt quickly. In fact, Birmingham – where the 1st Southern General Hospital was located – reorganised its system so efficiently that it was used as a model for other mobilisation hospitals.

‘Before the war, there was a system that was well-organised and was working fine, and then when the war started, it was completely disrupted,’ says Jonathan. ‘By the end of the 19th century, Birmingham was calling itself the “second city” and had set itself apart from other provincial cities by having a network of hospitals: as well as two general hospitals, the Queen’s and the General, there were lots of specialist hospitals, such as the Orthopaedic, Children’s, Women’s and Dental hospitals. The University also had a medical school. So this was why Birmingham was chosen as one of the key centres when the War Office drew up its mobilisation scheme in 1907.’

With a large pool of trained medical staff to draw upon, the University’s Great Hall was receiving its first military patients by October 1914.

But despite the relative wealth of medical knowledge in Birmingham, ‘miracle’ drugs such as penicillin to deal with infections hadn’t yet been invented and many of the drugs doctors had hitherto relied on were made by German pharmaceutical companies like Bayer and therefore unavailable due to the interruption of European trade brought about by the war.

‘So what you saw was a shortage of even standard medicines,’ says Jonathan. ‘That is why one of the annual reports from the hospital contained a list of herbs for people in Warwickshire to grow. Donors were also requested to supply old sheets for bandages. In some senses, then, people were forced to go back to an earlier form of medicine.’

And, of course, the more war casualties that arrived, the less able doctors were to treat the local civilian population.

‘Birmingham General Hospital, for example, set aside 100 beds for soldiers, which meant 100 fewer beds for the local population.

‘On the other hand, before the war, hospitals had been struggling financially and now they were being publicly funded – Birmingham General received £3,000 annually for its war work – and many took advantage of this to start or expand services, such as setting up VD clinics.’

Medical staff also benefited from visits from overseas doctors who were temporarily based in the region and able to spot shortcomings in the system.

‘Up until the start of World War One, Birmingham’s medical staff had been very local. One of the best things that happened during the war was that medical experts came from outside and were able to see deficiencies in the system and to show local doctors where there was room for improvement. Local doctors would also have seen facilities abroad and been able to compare what they had experienced in Birmingham.

‘Overall, then, I don’t think you can say there was medical progress during the Great War – that came afterwards – but what you can say is that the medical professionals made the most of what they had at their disposal. The medical students of the day would have gone on to become highly competent doctors. Some of them, of course, would have drawn on these experiences in the 1940s.’